Introduction

Exhausted by the “excesses of Romanticism,” composers were inspired to revolutionize the dawn of the twentieth century with an entirely fresh, progressive musical style. The “sense of possibility” possessed by these composers, as historian Joseph Auner calls it, denotes rejection of the idea that everything must stay the same. In the wake of this widespread search for modernity, no singular, dominant movement emerged, but a whole host of new musical thoughts was born.

Inspiration was drawn from all different sources: other styles, other creators, other cultures, and so on. What resulted was a tradition of total blending between artistic styles, as evidenced by the works of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937).

Not only is Ravel the pioneer and mastermind behind many breakthroughs from the twentieth century, but his career wholly captures the eclectic character of this era. As this concert will surely demonstrate, the works of Ravel span across decades of experimental movements, from Impressionism to Exoticism to Expressionism popular music to all of the above combined.

The diverse range of style in Ravel’s compositions is largely the influence of connections he made, through which he gained exposure to many different modes of expression. With this understanding, this concert program has been designed around Ravel, as his career represents the unique interconnectedness of twentieth century styles, genres, cultures, relationships, and more.

Three compositions by Ravel will be showcased, distinct from each other in their representation of styles or techniques, as they span quite far across the many phases of his career. Each Ravel piece will also be premised by the work of another composer from his lifetime. In placing these composers beside each other, the goal is to compare how influences were shared between them.

Thus, this concert is eclectic in itself. The program does not pertain to one specific style, genre, or technique, but displays an entire narrative of creative exchange. We hope you will join us in honoring this tradition of interconnectedness, especially as it is iconic to the twentieth century.

Setting

This concert will take place on April 23, 2021 at 8:00 PM at the St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn, NYC, NY.

The concert will take place in the spring to symbolize the vibrancy and novelty of the turn of the century. Also, the concert will take place at night to honor the presence of specific imagery in some pieces. The most heavy-handed example of this would be “Nacht” from Pierrot Lunaire, composed by Arnold Schoenberg in 1912, which is featured in our first act.

The grand, arched windows of the St. Ann’s Warehouse will contribute to the mood by exposing an elegant nighttime view of the Manhattan skyline. Converted from a church in the 1980’s, this event venue is a “flexible, open space”1 that comes down to 1,000 square feet of bare canvas.

St. Ann’s Warehouse has been selected for this concert based on its versatility, an essential asset to the set-up of the space. The concept, here, is that audience members will be seated in entirely mismatched chairs, acquired from thrift shops, antique stores, storage units, or the bowels of people’s homes. The goal is to get as much variety of color, shape, texture, and size as possible so that the physical set-up of the space will parallel the themes of eclecticism in Ravel’s twentieth century works.

Meet the Artists

Orchestre de l’Opera National de Lyon

From Lyon, France, Orchestre de l’Opera National de Lyon, alongside their most recent conductor, Thierry Escaich, brings French authenticity to our concert, in keeping with Ravel’s background. Most importantly, the official residence of Orchestre de l’Opera National de Lyon is l’Auditorium de Lyon, also titled The Maurice-Ravel Auditorium, in honor of the composer himself. Although this orchestra primarily performs operas, the theatricality and melodrama that goes into their usual performances will surely suit Ravel’s provocative compositions.

Notes on the Program

“Pagodas”, from Estampes, composed by Claude Debussy (1903)

To discuss Maurice Ravel’s greatest musical connections and influences yet not mention Claude Debussy would be erroneous, as the two composers are constantly compared. For instance, a passage by Auner, describing the iconic 1920’s-1930’s Paris music scene, refers to Ravel as “the most famous French composer after Debussy.”2

Both Debussy and Ravel are strongly associated with nineteenth century Impressionism in accordance with the start of their careers at this time. As Ronald L. Byrnside’s journal article, “Musical Impressionism” examines, however, these comparisons have been negative on occasion, including an “unfortunate and rather silly debate on the subject of influences and even plagiarism [between their works].”3 In response, Byrnside suspects that onlookers only conflated the separate works of Debussy and Ravel because they are both distinct and unique in contrast to other Impressionist works. In other words, Debussy and Ravel’s late-nineteenth century compositions are only similar in their dissimilarity to other Impressionist pieces; they are dissimilar from each other, too.

Regardless, links between Debussy and Ravel continued to emerge through the twentieth century, as exemplified by the two Exoticist pieces performed here: Debussy’s “Pagodas” from Estampes, and Ravel’s “Asia” from Scheherazade, both composed in 1903.

“Asia”, from Scheherazade, composed by Maurice Ravel (1903)

The Exoticism movement took off in the first decade of the twentieth century, a product of the “sense of possibility” held by composers in their quest for modernity. As the name suggests, Exoticist pieces borrow techniques and aesthetics from “exotic” or foreign cultures. Usually, these were cultural styles of the “Orient,” an outdated blanket term that ignorantly lumped all non-Western cultures together.

In fact, “Asia” from Scheherazade, composed by Maurice Ravel in 1903, is directly inspired by a Tristan Klingsor poem that revolves around “fantasies of a vaguely defined ‘Orient’ with references to Persia, China, and India.”4 To best channel this oriental style, Ravel applies musical techniques superficially associated with Asian and Middle-Eastern music, including pentatonic melodies and augmented seconds. In effect, Ravel’s application of “unusual spices”5 makes a noticeable statement when placed into a Western context.

Differently, in “Pagodas” from Estampes, composed by Claude Debussy in 1903, Debussy seeks to “expand and transform his own musical language”6 by incorporating Asian style more fluidly into the Western pallet. Inspired by his fascination with Japanese prints and engravings, Debussy took great care to emulate this aesthetic, even through the presentation of the title page. In sum, while both Ravel’s “Asia” and Debussy’s “Pagodas” speak to the Exoticism movement, they demonstrate two different methods of combining the “Orient” and the West.

“Nacht”, from Pierrot lunaire, composed by Arnold Schoenberg (1912)

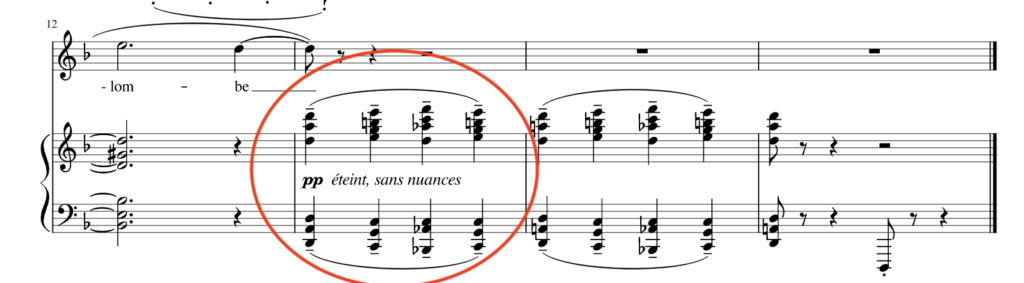

Another noteworthy revelation in the twentieth century was that of atonal and dissonant music, as seen in Expressionism and Serialism. The atonality movement launched post-World War I, as artists were eager to discard earlier conventions in this new chapter. “Nacht” from Pierrot lunaire, composed by Arnold Schoenberg in 1912, is the perfect example of these elements in action. Modeled from a series of poems, also titled Pierrot lunaire, written by Albert Giraud in 1884, Schoenberg crafted a musical melodrama with expressionist tones.

“Nacht,” a short, dramatic piece, was specifically selected for this concert as it perfectly captures the mood of Pierrot lunaire: vivid, dark imagery channeled into howl-like singing.

In relation to Ravel, and his career as a composer, Schoenberg’s work was very inspirational amidst the atonal movement. Like others, Ravel was interested in experimenting with unconventional sounds, exhausted by the extravagances of pre-war musical traditions. Chansons madécasses, composed by Maurice Ravel in 1925-1926, will demonstrate Ravel’s exploration of these new styles.

Chansons madécasses, composed by Maurice Ravel (1925-1926)

Chansons madécasses, composed by Maurice Ravel in 1925-1926, indicates a post-war shift in his composition techniques, which Henry Prunières, in his review of the composition, identified to be “more linear, thinner in texture, more contrapuntal.”7 Others have speculated that Chanson madécasses contains hints of Ravel’s Exoticist style, specifically in his use of calabash, a percussion instrument common in African music. The title Chanson madécasses also translates to “Madagascan songs” in English.

There is limited information on how Ravel perceived his own change in style, except that he has credited Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire as inspiration,8 which is why these two pieces are juxtaposed in our program. Both feature vulgar imagery, based on poetry, through a melodramatic interpretation of the melody by a female vocalist.

In particular, Ravel’s Chanson madécasses is described to be erotic, seductive, and dramatic. One wonders if Ravel was simply provocative in nature, as supported by his aforementioned unique Impressionist and striking Exoticist works.

Parade, composed by Erik Satie (1917)

As outlined by Auner, Parade, composed by Erik Satie in 1917, was an extremely successful albeit scandalous ballet which exercised “peculiar combinations of materials and nonchalant tone,”9 foretelling of 1920’s and 1930’s musical trends. Tending towards the category of popular music with its ragtime influences and danceable feel, Parade is made accessible to wider audiences through its embodiment of both “a musical hall variety show and a traveling circus” and its “motley cast of acrobats.”10 This piece offended some listeners with its vulgarity, however, especially during the sensitive time of World War I.

Cue the similarly, notoriously provocative Maurice Ravel. Evidently, Ravel and Satie ran in similar circles throughout their careers. Ravel, alongside Debussy, even took Satie under his wing early on.11 As critic Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi recalls, Ravel “[asserted] that Satie’s music contained the germ of many things in the modern developments of music”12 early on.

Clearly, Satie and Ravel demonstrate how composers each built upon their “senses of possibility” by inspiring each other. For instance, the following piece, Piano Concerto in G, composed by Maurice Ravel in 1931, is similar to Parade in its use of popular music styles, such as dance music and jazz.

Piano Concerto in G, composed by Maurice Ravel (1931)

“[Piano Concert in G] illustrates the heterogeneous mix of elements that [Ravel] was able to incorporate in a single work, including Classical forms, the retrospective genre of the concerto, the harmonies and timbres of jazz, and and sharp-edge, Machine Age style.”13

Piano Concerto in G, composed by Maurice Ravel in 1931, is even considered to be “Gerwishinesque” at times, referencing popular American jazz composer, George Gershwin. Just like Satie’s Parade, Piano Concerto in G signifies the rise of popular music to prominence in the 1920’s and 1930’s, including genres like dance music, blues, ragtime, and jazz.

It has been proven, simply by the nature of this concert program, that Ravel was keen to experiment with modern sounds. The impressive extent of his social network, as well as the impressive duration of his relevance within the sphere of twentieth century music, may be wholly attributed to his perpetually-open mind. It has been proven that Ravel was not afraid to experiment with new techniques and styles, and the provocative nature of his work contributes to his legendary renown. In this way, compositions by Ravel perfectly represent the daring, eclectic, and progressive personality of twentieth century music.

Notes

1. “Facility Rentals.” St. Ann’s Warehouse, https://stannswarehouse.org/about-st-anns-warehouse/facilities/

2. Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2013): 108.

3. Byrnside, Ronald L. “Musical Impressionism: The Early History of the Term”, (The Musical Quarterly, 1980): 534.

5. Auner, Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries: 29.

6. Ibid.

7. James, Richard S., “Ravel’s ‘Chansons Madécasses:’ Ethnic Fantasy or Ethnic Borrowing?” (The Musical Quarterly, 1990): 370.

8. Ibid., 361.

9. Auner, Twentieth and Twenty-First Century: 103.

10. Ibid.

11. Laloy, Louis, “La Musique retrouvée,” (Librairie Plon, Paris, 1928): 258-259.

12. Calvocoressi, Michel-Dimitri, “Erik Satie. A few recollections and remarks”, (The Monthly Musical Record, 1925): 6-7.

13. Auner, Twentieth and Twenty-First Century: 109.

Sources

Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2013.

Byrnside, Ronald L. “Musical Impressionism: The Early History of the Term.” The Musical Quarterly 66, no. 4 (1980).

Calvocoressi, Michel-Dimitri, “Erik Satie. A few recollections and remarks”, The Monthly Musical Record, 55, January 1, 1925.

James, Richard S. “Ravel’s ‘Chansons Madécasses:’ Ethnic Fantasy or Ethnic Borrowing?” The Musical Quarterly 74, no. 3 (1990).

Laloy, Louis, “La Musique retrouvée”, Librairie Plon, Paris, 1928.

St. Ann’s Warehouse. “Facility Rentals.” Accessed December 18, 2020. https://spektrix-nyc.do.stannswarehouse.org/about-st-anns-warehouse/facilities/.