At the turn of the century, the panicked urge felt by many composers to create a new tradition of music could not have occurred without a “sense of possibility.” The observation that some possess a “sense of possibility” originates from Musil’s Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften, which describes motivation to oppose the notion that everything should stay the same. According to Professor Joseph Auner, however, “even the possibility of a sense of possibility was by no means available to all.”1 Social conventions limited access to educational and professional opportunities for many in the twentieth century, as was demonstrated specifically by the difficulty women composers faced in their careers. Studying women composers Alma Schindler and Lili Boulanger as examples, it is clear that their high social statuses allowed for more success than many others could achieve, but they still experienced difficulty along the way, due to the negative perception of femininity held by many in the field of music.

Alma Schindler’s and Lili Boulanger’s successes were anomalies, since women composers in the twentieth century were challenged by a lack of resources, lack of encouragement, and lack of freedom from the stifying expectation that women remain primarily in a domestic role.

Upon their engagement, Schindler’s husband Gustav Mahler “made it clear that [Schindler] was to live for his music, not hers” and advised that she stop composing; he found the idea of a husband-wife composing team “ridiculous” and “degrading”.2 Mahler would often escape to his “composing hut” as a “withdrawal from the domestic sphere” when he needed creative inspiration. Mahler’s disposition towards his own wife embodies the widespread social belief that women were characterized by their rigid domestic roles, contrasting men’s liberties as careerists.3 Only after Schindler’s affair with architect Walter Gropius did Mahler take an interest in Schinder’s writings, regretting his previously neglectful attitude. Clearly, such negativity did not stop Schindler’s fiery creativity and wit; she even threw critique back in Mahler’s face, notably describing his First Symphony as “irritating” and “an ear-splitting, nerve-shattering din.”4

Quite differently, Boulanger never married nor had children, passing from chronic illness at the young age of twenty-four. Her sister, Nadia Boulanger never married either, but claimed that she was “married to her music”, so she lived on to tirelessly promote Lili’s compositions while achieving her own success as music teacher and composer. Since women were perpetually stifled by the rigidity of their domestic responsibilities, the accomplishments of the Boulanger sisters suggest that they prospered from this unconventional break from gendered expectations.

Educational opportunities also contributed to the success of the Boulangers, considering the sisters were “born into an exceptionally musical family.”5 Notably, the privilege of high education would determine a composer’s potential regardless of their gender, but a lack of education was more common among women, acting as a primary roadblock. Echoed by Schindler’s diary entry in which she hopelessly attributes the perceived impossibility of a career in music to the fact that her “mind has not been schooled,” the sexist expectation that women serve solely domestic purposes made access to education “terribly difficult for girls.”6 Like Schindler, women even had low expectations for themselves, since a successful career as a woman composer was otherwise unprecedented.

With a deeper understanding of Schindler’s and Boulanger’s career paths, it is interesting to analyze their compositions. Similar uses of symbolism, expressiveness, and irresoluteness can be considered representative of their similar experiences and creative ideas.

As a first example, Clairières dans ciel, composed by Boulanger in 1914 and published in 1919, reflects sorrowfully upon the parting of two lovers. This thirteen-piece movement channels Francis Jammes’s poetry in expressive, melancholic melodies, specifically in symbolism-rich Song 12, “Je garde un médaille d’elle”.

Je garde une médaille d’elle

Je garde une médaille d’elle où sont gravés

une date et les mots: prier, croire, espérer.

Mais moi, je vois surtout que la médaille est sombre :

son argent a noirci sur son col de colombe.

– Francis Jammes (1906)

I keep a medal for her

I keep a medal for her on which are engraved

three words: pray, believe, hope.

What I see most is that the medal is dark because

its silver has blackened on her dove’s neck.

– Francis Jammes (1906)

Lili Boulanger’s interpretation of Jammes’s writing is thought to be so emotional that her sister Nadia identified a connection between the poem’s young female love interest and Lili herself.7 Given this apparent bond, musicologist Bonnie Jo Dopp wonders in her interpretation of Clairières dans ciel if “Lili experienced such unhappiness in love”8 as is depicted in the poem.

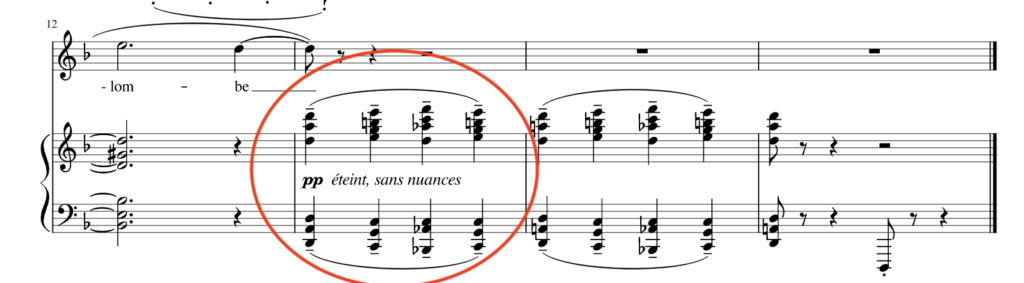

The emotion behind Boulanger’s composition is represented musically throughout the song, as exemplified in the irresoluteness of the cadence at m.12. Building up to a half cadence with a V7 chord of G, the line fails to resolve to the tonic and instead falls to D minor, sustaining through m.13.

For the listener, the avoidance of a clean, traditional resolution recreates feelings of hopelessness and dissatisfaction as provoked by lost love. Throughout the song, bitonal accompaniment chords also act as musical representation, mirroring two mismatched lovers. Boulanger even creates visual symbolism, since the arrangement of the notes on the page forms the circular shape of une médaille, or a medallion as is featured in the lover’s memories.

Also riddled with deeply-felt emotion is Schindler’s “Die stille Stadt”, composed in 1910, inspired by Richard Dehmel’s dark and expressive poem. In accordance with this poem’s depiction of a hopeless, quiet night from the perspective of a wanderer, Schindler was repeatedly “drawn to mysticism and the contemplation of inner life”9 as a subject.

Die stille Stadt

Liegt eine Stadt im Tale,

Ein blasser Tag vergeht.

Es wird nicht [lange dauern mehr]1,

Bis weder Mond noch Sterne

[Nur Nacht] am Himmel steht.

Von allen Bergen drücken

Nebel auf die Stadt,

Es dringt kein Dach, [nicht] Hof noch Haus,

Kein Laut aus ihrem Rauch heraus,

Kaum Türme noch und Brücken.

[Doch] als dem Wandrer graute,

Da ging ein Lichtlein auf im Grund

Und [durch den] [Rauch und Nebel]

Begann ein [leiser] Lobgesang

Aus Kindermund.

– Richard Dehmel

The Silent Town

A town lies in the valley;

A pallid day fades.

It will not be long now

Before neither moon nor stars

But only night will be seen in the heavens.

From all the mountains

Fog presses down upon the town;

No roof may be discerned, no yard nor house,

No sound penetrates through the smoke,

Barely even a tower or a bridge.

But as the traveller became filled with dread

A little light shone out,

And through smoke and fog

A song of praise began,

Sung by children.

– Richard Dehmel

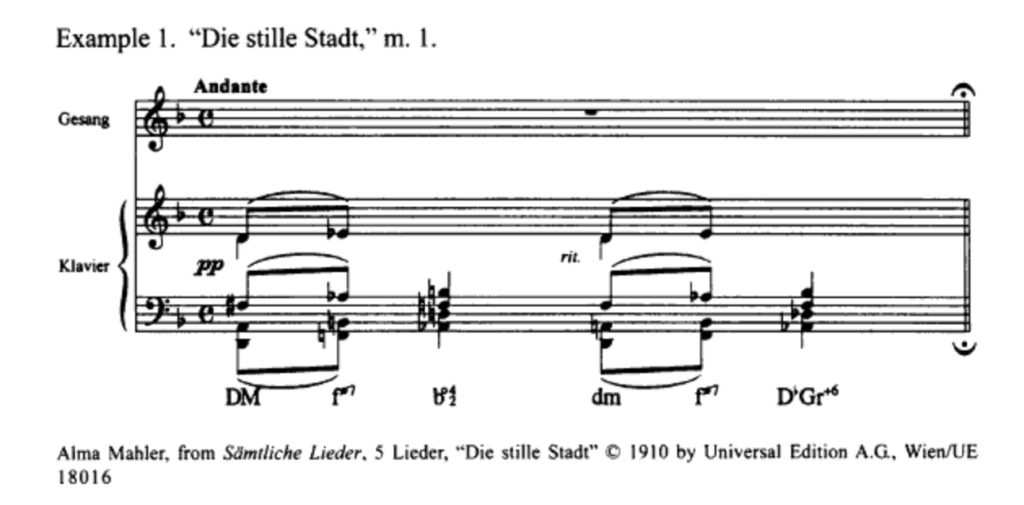

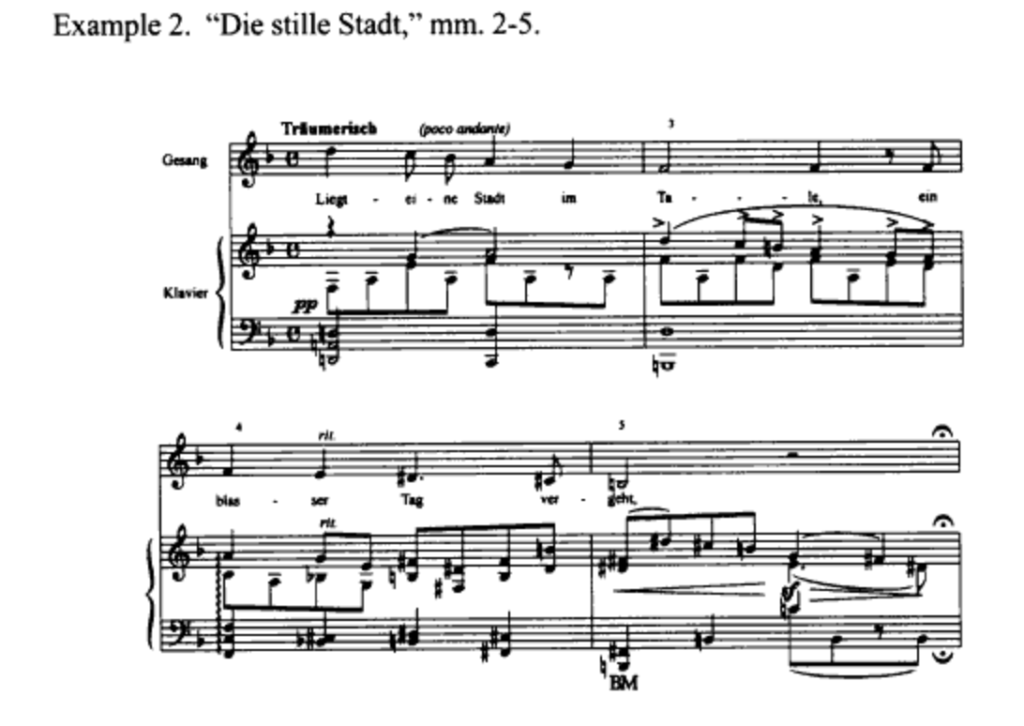

Schindler’s compositions regularly channeled themes of “night versus light, loneliness and love, and sexual union as a spiritual communion,”10 marrying vivid imagery with her provocative style. Just as Boulanger strategically avoided conventional resolution, Schindler instills a sense of uneasiness in “Die stille Stadt” with phrases that deliberately cut off in the middle of their flow.

Schindler immediately creates a dreamlike sound on the upbeat of beat 1, m.1 with use of Wagner’s unconventional and unresolved “Tristan” chord, an iconic feature of twentieth century music. Throughout her compositions, Schindler exemplifies an affinity for unconventional harmony and chromaticism, with rare appearances of major and minor chords and frequent uses of augmented and diminished chords, like the “Tristan chord”.11 Also similar to Boulanger, Schindler uses musical representations to emotionally provoke the listener as, in m.2-5, a chromatic descending line accompanies the sunset in the poem.12

“Je garde une médaille d’elle” by Boulanger and “Die stille Stadt” by Schindler clearly share deep expressions of melancholy and evocative uses of musical representation. More notably, however, these songs are comparable in their roles as emotional, creative outlets for women composers in a time when it was rare for them to be published. Knowing that both women experienced such hopeless struggles in the pursuit of composition and beyond, it is possible that the morose and lonely moods of these songs are channeling their trying experiences.

In twentieth century music, such blatant imbalance of opportunity between genders was heavily tied to widespread negative perceptions of women, only perpetuated by influential men composers of the era. American composer Charles Ives, for example, was notoriously sexist and used gendered terms to emphasize the flaws he saw in musical tradition. To criticize nineteenth century music, he described its outdated urban, cultivated quality to be effeminate; instead, he sought the “masculine authenticity” of more rough and vernacular music.13 As a result, many positive musical innovations were labeled “masculine”, beginning a tradition which effectively “depreciated and suppressed styles that were regarded ‘feminine’, along with the contributions of women composers, musicians, and patrons.”14 Establishing a negative association with femininity was especially impactful when used to slander outdated music in the twentieth century, since a desire for new, modern music practically characterized the era.

The field of music only furthered demeaned femininity in its associations with the weak, domestic, and inferior. Though subtle, the perpetuation of these gender stereotypes only further discouraged women composers from confidently pursuing careers. This negativity is prominent in Schindler’s childhood diary entry in which, after losing hope of finding a woman composer role model, she defeatedly declares “a woman can achieve nothing, never ever.”15

Given the discriminatory trials women endured when pursuing careers in music, there is notably irony in the twentieth century search for progress and artistic renewal. How progressive is a movement that excludes women, along with several other groups who could not afford opportunities for success at this time? A “sense of possibility” is clearly selective in its ability to inspire and mobilize. Thankfully, though, with Schindler and Boulanger to act as a few exceptions, these women composers broke social boundaries, ultimately contributing to the prominence of women in music today.

Sources

Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2013. Print.

Dopp, Bonnie Jo. “Numerology and Cryptography in the Music of Lili Boulanger: The Hidden Program in ‘Clairières Dans Le Ciel.’” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 3, 1994.

Follet, Diane. “Redeeming Alma: The Songs of Alma Mahler.” College Music Symposium, vol. 44, 2004, pp. 28–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40374487. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020.

Potter, Caroline. Nadia and Lili Boulanger. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016.

Rosenstiel, Léonie. The Life and Works of Lili Boulanger. Rutherford, N.J: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1978. Print.

Notes

1 Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. (W.W. Norton & Company, 2013): 8.

2 Follet, Diane. “Redeeming Alma: The Songs of Alma Mahler.” (College Music Society, 2004): 29.

3 Auner, Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries: 17.

4 Ibid., 24.

5 Potter, Caroline. Nadia and Lili Boulanger. (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016): xi.

6 Auner. Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries: 25.

7 Rosenstiel, Leonie. The Life and Works of Lili Boulanger. (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1978): 276.

8 Dopp, Bonnie Jo. “Numerology and Cryptography in the Music of Lili Boulanger: The Hidden Program in ‘Clairières Dans Le Ciel.’” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 3, (1994): 560.

9 Follet, “Redeeming Alma”: 30.

10 Ibid., 31.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., 34.

[13] Auner, Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries: 64.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.